Complex Lessons from Living on the Road

- Stevie Gray

- Nov 26, 2025

- 15 min read

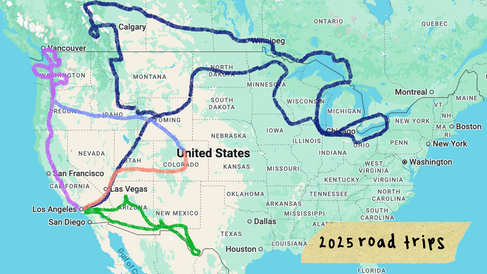

I’m writing this as I prepare to return from the longest and most intense road trip we’ve ever done.

In 35 days, we visited 10 new US states, 4 new Canadian Provinces, 10 new cities, and 11 new National Parks while on the road. In total, we’ve estimated that we drove for over 150 hours. This trip was twice as long as our previous longest trip, with our furthest points from Los Angeles being Toronto, ON and Jasper, AB.

And, this is just one of a few roadtrips that we've taken this year.

Over the course of the last 5 years, my wife/life partner Marcela Riddick and I have spent collective months living on the road while traveling across the contiguous United States.

To date, we've explored 24 US states while living in our car and have visited over 40 National Parks and Monuments, which we often use as stops while on route.

As we were experiencing the hottest, buggiest, and most climate and regionally diverse trip we’ve ever taken, I couldn't help but reflect on how much I’ve grown to love every aspect of road tripping, and how much my passion and understanding of both the natural world and the history of North America have grown as a result of our many trips.

While we love these trips, there’s a great contradiction. In an attempt to see as much of the natural world as possible, we’re driving a fossil fuel-powered vehicle thousands of miles through regions defined by historic injustices and climate hardships.

This article will contain very specific perspectives. I am by no means an example of perfect environmentalism. If anything, I’m a product of a world designed without the environment in mind. It took years of learning and growing for me to begin to understand many of the intertwining problems with my car-centric lifestyle.

However, if it weren’t for my formative years being spent in a car, I likely never would have grown to love roadtrips, and in turn, I likely never would have gained such a deep passion for the natural world and environmental equity.

A Relationship with the Automobile

The majority of my childhood experiences involved a car. In Miracle Mile, Los Angeles, a pocket of the city literally designed to be viewed from the automobile, if you’re going somewhere, you probably aren’t walking. Whether we were driving someone to school, practice, or we were visiting family in the Bay Area for the holidays, I spent a large portion of my early years in the back row of my family’s minivan, annoying my two older siblings.

One of the most exciting accomplishments of my teenage years was getting my drivers license. Like many of my friends, I got it as soon as I possibly could. It meant I could finally go anywhere on the road, and to some extent, it unlocked the entire map of the United States. All of the sudden, I was in the driver’s seat of the minivan, and it was awesome.

I never thought much about the negative impact of automobiles on our planet. My entire world was designed for cars, and any messaging I saw about cars was positive.

The Dodgers, LA’s biggest team, is sponsored by 76 gas. I played with Chevron-branded toy cars as a toddler, and I grew up skateboarding in giant parking lots. Even to this day, the smells of gasoline and hot asphalt are nostalgic.

“As people who care a lot about conservation but grew up in concrete, it’s a very different connection that we have to land than other people do. We [can] be super pro-resource management and pro-land, but not understand what it takes to live on that land.” - Marcela Riddick, on connection to land, 2022

A car-centric city rarely exists in balance with the natural world, and this is very true of Los Angeles. One of the most effective ways to highlight this phenomenon is by turning on “street view” for Google Maps, which highlights every road in a bright blue color.

Very quickly, any patches of the natural world become islands, cut off by an ocean of roads, freeways, and interstate highways.

Our roads not only disconnect humans from nature, they disconnect entire ecosystems, making instinctual migration patterns for species like mountain lions much more dangerous, which is why investment in infrastructure like the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing is vital.

Our Roadtripping Origins

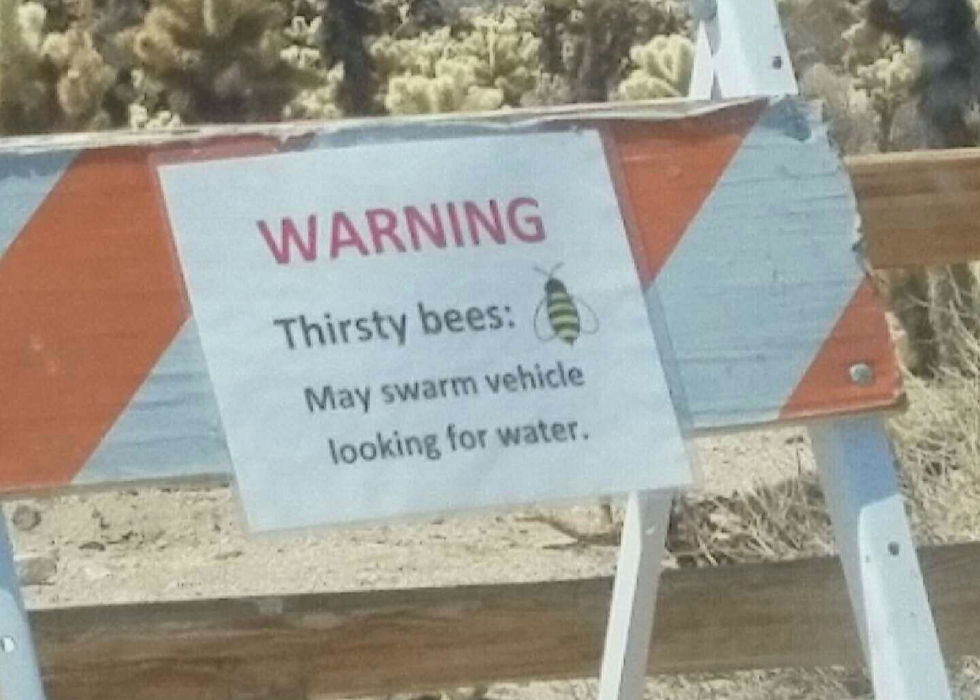

The first National Park I ever went to was Joshua Tree. It was the first time Marcela and I drove somewhere alone and spent the night away together. It was a particularly hot summer during the drought years in 2016, and we had just graduated high school. In the park, we saw a sign that said “WARNING, thirsty bees.” We thought it was hilarious.

That random moment was a small taste of how many out of the ordinary life experiences we were about to have on the road together.

Our entire relationship was built on long conversations. We became best friends by spending every recess sitting at the lunch tables talking, making fun of each other, and watching an orange that we had thrown into a drainage pipe decompose.

Sitting in a car for hours didn’t feel much different. If anything, the views on the road were way more interesting than a grassless black top schoolyard.

We ended up going to college in Fort Collins, Colorado, a 16 hour drive from Los Angeles, and in my opinion, one of the best 16 hour stretches in the American West.

First, you drive through the Mojave Desert, one of the hottest places on Earth, and a truly martian environment. Then, you drive through Utah's gorgeous red rock canyons, the "Radiator Springs" kind. Then, you pass through the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, an expanse of giant peaks, forests, and glaciers. Finally, you’re in the Great Plains of North America, where tens of millions of bison once grazed.

From 2017-2019, the routes between Los Angeles and Fort Collins were our testing grounds for road tripping. We went as many new ways as we could, passing through states like New Mexico, Wyoming, Arizona, and Nevada on a combination of highways.

The Environmental Cost of Adventure

I should address the elephant in the room. It’s time to dive into our first complex topic; the environmental ethics of road tripping.

“How can I call myself an environmentalist as I drive my gas-powered vehicle into forests, coasts, and deserts?” is a question I've asked myself many times in recent years.

Maybe I can’t.

However, if I wanted to call myself an environmentalist and still visit these parks, there’s a problem; it’s physically impossible to see National Parks without taking a combination of cars, buses, trains, or planes.

So, every time I drive into the great outdoors, am I part of a global emissions problem? According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, “cars and trucks account for nearly one-fifth of all US emissions, emitting around 24 pounds of carbon dioxide and other global-warming gases for every gallon of [gasoline].”

While the carbon footprint of traveling by plane is often higher, our car-based footprint isn't negligible.

So, what do we do with this information? Do we stop going on road trips until we can afford an electric vehicle, which is currently an unattainable luxury for millions of people?

This is a similar problem to that of equitable food, where the cost of eating organic, locally grown produce can often be a luxury.

Outdoor Equity

When we begin to dissect what seeing the “great outdoors” really means, it quickly becomes clear how inequitable access to the natural world is.

Like many issues, understanding the intersectionality of outdoor equity is vital to understanding the number of solutions that need to happen in tandem.

Many outdoor equity issues are tied to historic and ongoing racial injustices. According to a report by the Center for American Progress titled The Nature Gap, "Communities of color are three times more likely than white communities to live in nature-deprived areas." These communities are often ones that were historically redlined (NPR).

There are a number of outdoor equity-focused organizations that are working toward solutions. Groups like Outdoor Afro, Latino Outdoors, Indigenous Women Hike, and Diversify Outdoors are working tirelessly to close the gap.

When it comes to car camping specifically, equity issues only continue to get more complicated.

If you wanted to see the National Parks of the United States through road trips, you need a car; but not just any car. You need a car that’s able to handle thousands of miles on the road. The fuel and maintenance will be an ongoing expense.

Next, you have to decide where you’re sleeping. The most affordable option is to sleep in your car, but do you have the gear to make that comfortable? Are you short enough to even fit in your car? Are you traveling with people you want to sleep in a car with?

If car camping isn’t an option, you could tent camp. Do you have a tent, or do you have to purchase one? If you don’t have a tent and don’t want to tent camp, the next option after that is to sleep in a motel.

With expenses everywhere, it’s apparent that road tripping's equity problem is also socioeconomic. While an argument can be made for the affordability of road tripping compared to air travel and hotel expenses, if you're traveling with family, you'll likely need to rent a larger vehicle and purchase more gear.

Lastly, another important barrier to entry for the outdoors: comfortability. If you haven't camped before, there's a good chance that your first camping experience is going to be very uncomfortable.

Learning to Camp

I didn’t grow up camping, at all. My first camping experience was with Marcela and her family during our senior year of high school, exactly ten years ago. We spent a couple nights at a campground in Lake Cachuma, California. While I had fun, it was all very new.

As we started college, we went on a couple more camping trips. There were a number of uncomfortable moments, lessons learned, and failed experiments along the way; but, after a lot of forced-exposure, lessons from friends who were studying animal science, and some inspiring lectures in a wildlife conservation class, I began to see the appeal of being in the dirt in the middle of nowhere.

Throughout all of those new experiences, something I couldn’t wrap my head around was the idea of setting up a tent right next to your car.

I could understand backpacking, where you hike your tent into the forest with you, but if you’re going to be a couple meters from your car, why not just use it as a metal tent?

On top of that, since our trips often had multiple stops, being able to wake up, crawl into the driver’s seat, and head out from a campground would save hours every day. If we have a 10-hour drive ahead of us, the last thing we want to do is break down and pack a tent beforehand.

Learning to Car Camp

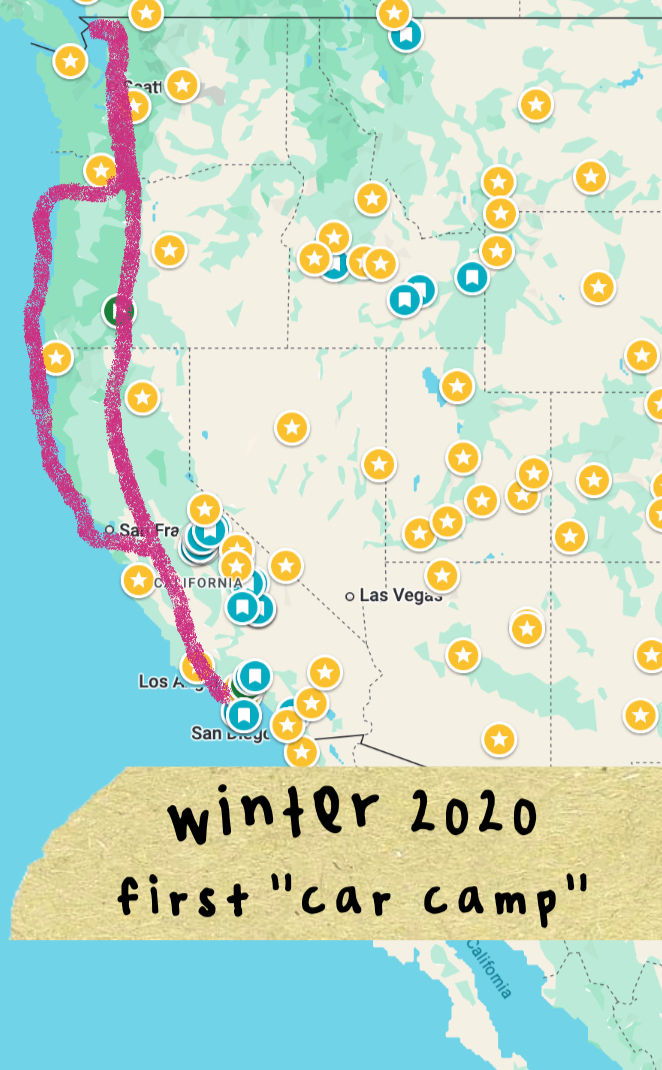

Although we had been driving long distances for years, we didn’t intentionally camp in our car for the first time until the winter of 2020. The route was a loop from Los Angeles to Camano Island, Washington. At that point in time, it was our longest route ever.

On the trip, we got a small tease of the Pacific Northwest’s incredible beauty. On top of that, we encountered some of the most dangerous road conditions we’ve seen to this day.

After leaving Portland, Oregon later than expected (my bad), we drove through an intense rainstorm in Tillamook National Forest. It was pitch black, and I remember only being able to see a couple feet in front of the car as we weaved through the forest. It was an exhausting couple hours of winding roads, heavy rain, and low visibility.

Once we got out of the forest, we pulled up to a campsite by the ocean. We couldn’t see anything around us, and it was still pouring. As we prepared to sleep on our inflatable mattress and peed on bushes in the rain, we couldn’t help but laugh. Our adrenaline was reaching a unique high; somehow, we were having fun.

That trip was an evolutionary stage for us. If we could enjoy that night, the possibilities felt endless.

Public Land in the American West

We continued to take trips into the forests and coasts of California for the next couple years, experimenting with gear, weather and climate conditions, along with bringing our dog Walter with us. Whether we were sleeping in our car during heat waves in the Central Valley or in harsh winters in the Mojave desert, we were adapting and exploring new regions.

Along the way, Marcela taught me about BLM (Bureau of Land Management) campsites, where we could essentially pull up on a whim and have a place to sleep. With no need to book a site or set up a tent, we could plan our road trips as they were happening.

Many of the most incredible natural landscapes we’ve seen in the American West are on these public lands, and as of June 2025, over 250 million acres were at risk of being sold and developed due to the Senate Reconciliation Bill.

Over the years, I had grown to believe that future generations would have more access than we did to natural landscapes; however, the opposite may be true. If we don't continue to advocate and organize for the protection of these lands, future generations will likely be born into a world with less biodiversity than we have now.

“The Big Trip”

During our 10th anniversary trip to Joshua Tree in December, 2021, we learned about National Parks passes for the first time. For an annual fee of $80, you’re able to enter any National Park or Monument in the United States.

With the goal of making the most out of our new pass, as we were getting ready to graduate in the Spring of 2022, we planned our biggest trip yet.

It started as “how can we get to Glacier National Park,” and quickly turned into, “Woah, we can hit 11 National Parks in one trip?”

So, we got serious about it. We built a platform in our car and bought used backpacking gear to sleep on. At over 70 hours of driving and 11 National Parks, we, along with our dog Walter, spent 21 days living on the road. It was easily the most fun I’d ever had in my entire life at that point.

We saw bears, bison, wolves, foxes, moose, elk, deer, snakes, and turkeys throughout an incredible range of biomes and climates in the West. In some moments, we experienced triple-digit weather, in others, we were freezing near iced-out roads and glaciers.

A friend of ours challenged us to capture the experience, which led to the creation of “On the Road," a live log of our thoughts on the trip. The episodes are a window into our typical conversations while on the road. I’m not a fan of my voice or being on camera, but it’s a gift to have those moments of our youth captured.

The Indigenous History We Weren’t Taught Growing Up

On the topic of National Parks and public land, it’s time to go through some history.

The National Parks and Monuments system was established to protect and preserve significant natural, cultural, and historic sites in the United States, and today, National Parks like Yosemite and Zion are world renowned for their unique and otherworldly views, attracting visitors from around the globe.

In the post-industrial context, the Parks represent some of the biggest “wins” in the history of wildlife conservation. But, the National Parks also represent one of the biggest tragedies in human history, too, as they represent the genocide and displacement of Indigenous people across the North American continent.

All of the regions of the present contiguous United States were home to expansive Indigenous civilizations and regional trade networks that had existed across the Americas for over 15,000 years (before the end of the last Ice Age). Obsidian traveled down from the Eastern Sierras to the coast of Southern California, and tropical bird feathers from central Mexico have been found in sites in the state of New Mexico and Utah.

After colonization, genocide, and the displacement of Indigenous people by a number of European nations and the United States, many of the only protected remnants of that period in history can be found in National Parks and Monuments.

With all of this history in mind, National Parks and Monuments are complicated. In addition to being truly beautiful natural spaces and historic sites, they have been cultural centers for thousands of years for Indigenous people. In that way, National Parks represent a terrible injustice.

This history quickly became apparent as we made our way through our “Big Trip" in 2022. We continued to see Indigenous history on park brochures, on roadside signs, and at sites along the Southwest, all while passing through the land of the Shoshone, Blackfeet, Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, Diné, Ute, Ute Mountain Ute, Paiute, and Mescalero Apache.

Tribal Parks and Land Loss

While it's vital to understand Indigenous history, it's equally vital to understand that Indigenous history is still being written today.

One of the most important stops we ever made was near the “Four Corners” region of the Southwest, where Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona meet. We had just visited Mesa Verde National Park, which is home to an immense number of cliff dwellings and other pre-Columbian indigenous history.

On the side of the road heading toward Four Corners, we spotted the Ute Mountain Tribal Park Visitor Center and pulled off the road. Inside the visitor center, we were told the history of the Ute, and the relationship between the tribes of the Southwest and the National Parks.

The Ute Mountain Reservation has its own cliff dwellings in Ute Mountain Tribal Park, within the same canyon as Mesa Verde National Park.

Learning about the handful of Tribal Parks in the Southwest as examples of Indigenous sovereignty began a much deeper conversation about tribal history and ancestral land loss in the United States.

From a historical perspective, all of the borders in North America are new. As a result of broken treaties, the Indian Removal Act, national boundaries, state boundaries, and private land, historic tribal land has been split, displacing Indigenous people from their ancestral lands.

While visiting Arizona's Organ Pipes National Monument in 2024 near the US-Mexico border, we learned about the Tohono O'odham, a tribe that has been based in the Sonoran Desert for thousands of years. The tribe developed advanced agricultural practices and regularly migrated following climate patterns. As the region was colonized by competing powers, and most recently, when the international border was established, the tribe was directly impacted.

On countless occasions, the U.S. Border Patrol has detained and deported members of the Tohono O’odham Nation who were simply traveling through their own traditional lands, practicing migratory traditions essential to their religion, economy and culture. - Tohono O’odham Nation, History & Culture

Information like this is rarely taught in depth in United States classrooms, and as of this year, much of this history is actively under threat of being suppressed and erased, especially within National Parks and Monuments.

Through a recent executive order, "the [Trump] administration is forcing National Park Service staff to inventory its signage and interpretation to meet standards that are not based on historical scholarship or science" (National Parks Conservation Association, 2025).

If there is any hope of restorative justice, for both for these natural environments and the people that have called them home for thousands of years, this information must be taught in depth, learned, and protected.

The Spaceship Era: 2022-2025

With all of our learnings, the “Big Trip” was more formative than we could have ever hoped for. Plans changed on the fly, we covered stretches of over 10 hours a day, and we saw a significant portion of the American West.

If you had asked us if we wanted to continue living on the road, we would have happily said yes. Unfortunately for us, we had to return home to begin our adult lives and move out of our parent’s homes.

From that point on, our trips couldn’t have the same scope unless we were either unemployed or working remotely. But, we continued to go on trips each time we had the opportunity.

On average, our trips ranged from 1-2 weeks long, had a center point of a new National Park (with many along the way), and often covered about 40 hours of driving.

Because of typical breaks, many of our road trips were in the Winter. On those trips, we adopted the “spaceship” mentality, where our car was a safe, habitable vessel to travel through some of the harshest desert conditions. On trips like these, we experienced temperatures as low as -13 degrees Fahrenheit (-25 degrees Celsius).

From 2022-2025, we visited every state in the American West, and all but one National Park, Crater Lake in Oregon.

"The Great Trip"

I often plan road trip “loops” that use National Parks and Monuments as points of interest. One loop I had made a few years back centered around the city of Chicago, Illinois, and covered most of the remaining US states and parks that we have left to visit.

As I mentioned earlier, a month or longer trip is only feasible when we can work remotely, or if we’re unemployed.

With 2025 continuing to be unpredictable and messy, it turned out that we had the ability to complete the “Chicago Loop” this year. So, seemingly like a once in a lifetime opportunity, we went on our biggest road trip ever.

The trip began with the goal of crossing off nearly every U.S. National Park and state left, but evolved into a "Great Lakes" and "Great Plains" international route in an attempt to avoid uncomfortably humid temperatures in the American South. We've since dubbed it the "Great Trip."

There's a lot left to write about the Great Trip. We learned about the Great Lakes as inland oceans, Canadian history, wildfires, land management, and Indigenous history from the Rockies through the plains.

It was without a doubt the most challenging road trip we've ever completed. The route and duration changed many times, as did our life plans.

Even with the long drives, mosquitos, storms, and our illnesses throughout the 35-day experience, "The Great Trip" was truly great.

Reflections

As we step into the next era of our lives together, it's important to reflect on how much living on the road has taught us. From Indigenous history and outdoor equity to our personal carbon footprints and uninterrupted "scheming time," we've learned that "living on the land" often means coming to terms with the asphalt beneath us, and the injustices the land itself holds.

While at times uncomfortable, these contradictions and learnings will continue to shape our perspectives for years to come.

Stay tuned for updates and images from the road!

All images in this article were captured by Marcela Riddick and Stevie Gray.

Comments